Canada at a Crossroads – Volume 2: Baby Steps, How to reverse Canada’s falling fertility rates

THE CANADA AT A CROSSROADS SERIES

Canada is at a crossroads. The issues confronting Canada in 2025 go beyond mere setbacks and can more accurately be called crises. Unless they are resolved quickly, we face a deep and potentially permanent loss of our national standard of living and quality of life.

We hereby introduce the “Canada at the Crossroads” series of reports from the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Each one is a relatively short essay explaining the problem at hand and outlining potential solutions. This series will not propose minor tweaks to existing strategies, nor will it look only for modest course corrections. Canada is beset by incompetent governance, runaway and rampant ideology, social malaise, and a national identity crisis.

Its future is at stake – and the time for small, hesitant steps has passed. It is in this spirit that we invite readers to join us as we confront the problems facing our country and set out serious, disruptive ideas to make 2025 the year Canada began to step back from the brink.

VOLUME 2: BABY STEPS – HOW TO REVERSE CANADA’S FALLING FERTILITY RATES

By Ross McKitrick

March 6, 2025

Executive Summary

For decades Canada’s fertility rate has been below the level needed to replace the population, and in the past five years it has dropped even more sharply. Yet survey evidence shows that Canadian women would like to have more children than they do. We must address the issues that are preventing Canadians from achieving their family aspirations as they lie at the very core of our quality of life. This essay outlines the scope of our fertility crisis. It argues that immigration is not a solution, instead it just papers over the underlying problems affecting the lives of Canadians.

Most academic literature offers relatively little guidance since most of it has focused on how to reduce fertility in poor countries, not how to raise it in wealthy ones. An analysis of Canadian data leads to the following conclusions:

- Income growth has a strong, positive impact on fertility for almost all income groups except the wealthiest.

- Increases in the overall cost of living suppress fertility, and the effect appears quite strong. On the other hand, while the rising cost of housing has an adverse effect on fertility, it isn’t enough to be statistically significant.

- The effect of housing availability on fertility is ambiguous. The number of housing completions per thousand people has no apparent effect, whereas the fraction of housing units consisting of apartments does have a beneficial effect on fertility. Apparently what matters is not simply the number of new homes, but the types available.

- Even though the fertility data since 2016 show steep declines, the trend from 1991 to 2022 after controlling for other explanatory variables is slightly positive. This is encouraging because it means that after controlling for the factors that policy decisions can potentially affect the trend over time is slightly positive although insignificant.

An action plan to increase domestic fertility should include the following:

- Reducing the cost of living, especially housing and transportation.

- Lowering marginal income tax rates, improving per-child benefits, and allowing more income-sharing.

- Improving income replacement schemes under EI

- Taking measures to increase the availability of private (including home-based) child care services.

- Taking measures to shift social norms in favour of parenthood for both women and men.

One recommended change is to increase the marginal fiscal benefits associated with having more than two children. Current policy decreases benefits for families with more children, but to raise domestic fertility, options should be explored to encourage families who already have children to have more.

Additionally, it is important to focus on difficult-to-quantify cultural aspects that may contribute to the rapidly declining fertility. The government can take steps beyond merely fiscal measures to promote a family-friendly and pro-child society.

Introduction: The scale of the fertility crisis

There is a fertility crash underway in Canada and this paper argues that it is a major public policy challenge requiring immediate federal action. It is a public policy crisis for two reasons. First, there is a rapidly widening gap between young Canadians’ stated family ambitions and actual outcomes, which points to growing impediments to achieving one of the most vital contributors to well-being and life satisfaction. Second, attempts to sustain a viable working-age population through mass immigration create other problems and may not even succeed in maintaining a workforce large enough to fund our social safety net. The decline in the domestic birth rate is a problem in and of itself and Canada needs a far-reaching program of action to address it.

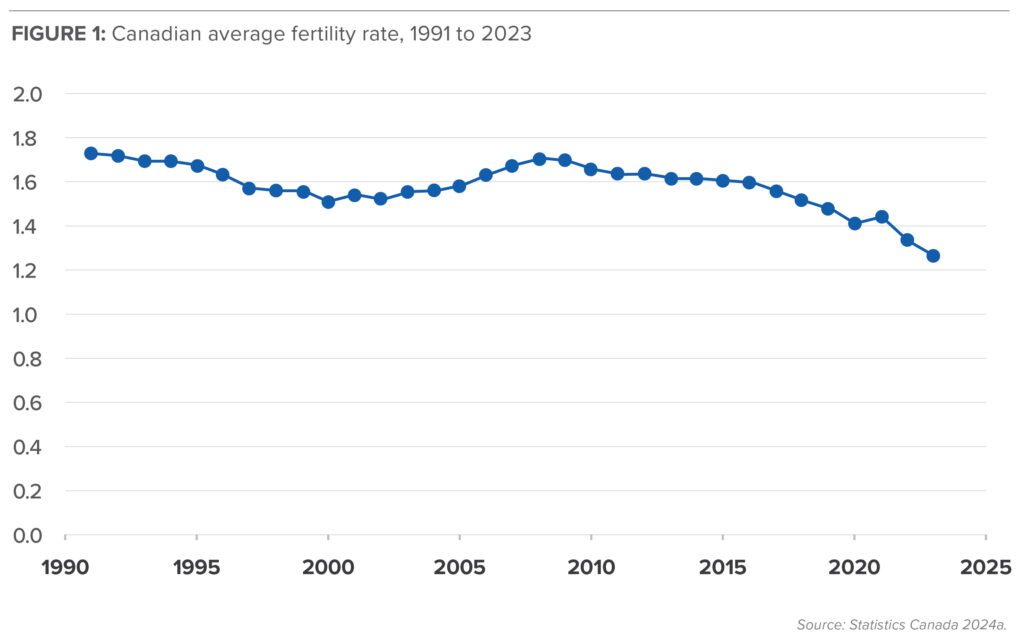

Canada’s birth rate has been well below the global average at least since 1950. Provencher and Galbraith (2024) note that the start of the drop-off in Canadian fertility coincided with the introduction of oral contraceptive pills in 1960. By 1971 we were below the replacement rate (2.1 live births per woman). After a plateau from 2010 to 2015 the downward trend began accelerating in 2016 and, notwithstanding a tiny post-COVID baby bump, Canada is now experiencing an unprecedented decline in its birth rate.

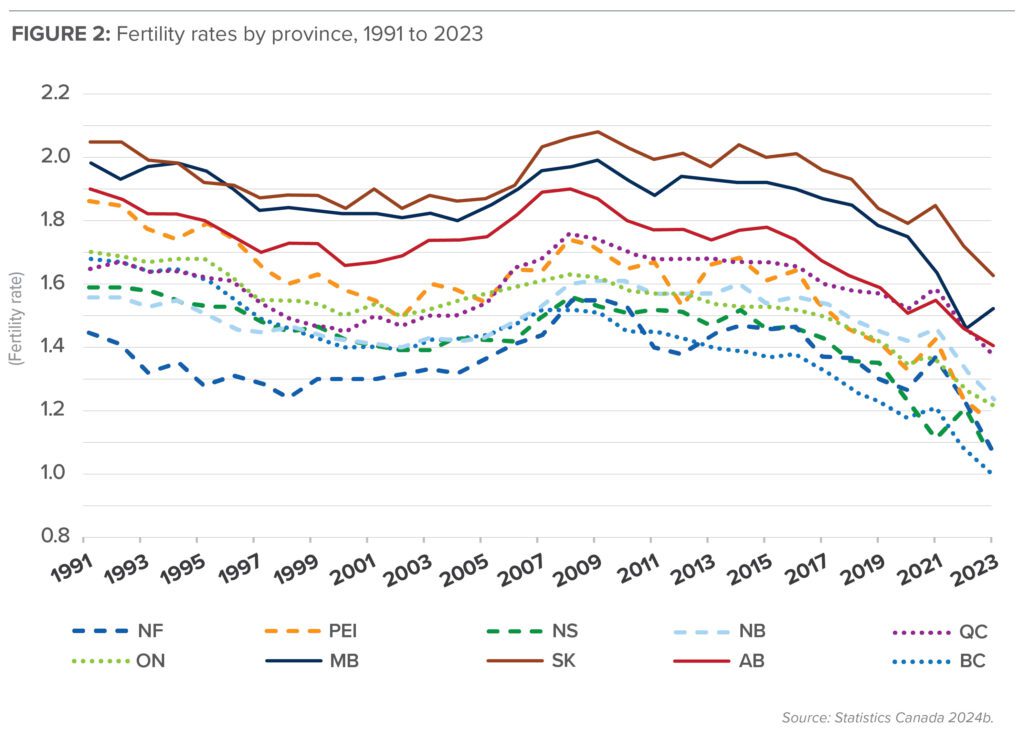

There are persistent differences among provinces, but as of 2016 each one was undergoing an identical fertility crash:

Stone (2023) presents survey evidence that even today, on average, Canadian women aspire to have two or more children. Therefore, the outcomes illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 imply a widening gap between the number of children Canadian families want and the number they actually are having. A large and growing gap in something as fundamental as family formation implies a threat to well-being that merits close attention.

The current (2023) fertility rates by province are detailed in Table 1.

The perimeter penalty

For some reason the birthrate is lowest in the western- and eastern-most regions – a so-called “perimeter penalty.” British Columbia has the lowest birth rate at 1.00 live births per woman. The Yukon is next at 1.01. Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island are the next lowest at 1.05, 1.08, and 1.16 respectively. The Prairie Provinces have persistently had the highest birth rates. Saskatchewan had a birth rate of 2.0 per woman as recently as 2016 but it has dropped sharply since then.

Ontario’s birth rate is 1.22 and Quebec’s is 1.38, both well below the replacement rate, and well down since 2010 when it was 1.58 in Ontario and 1.70 in Quebec.

Nunavut has been a persistent outlier, having maintained a fertility rate above replacement since its records began in 1999.

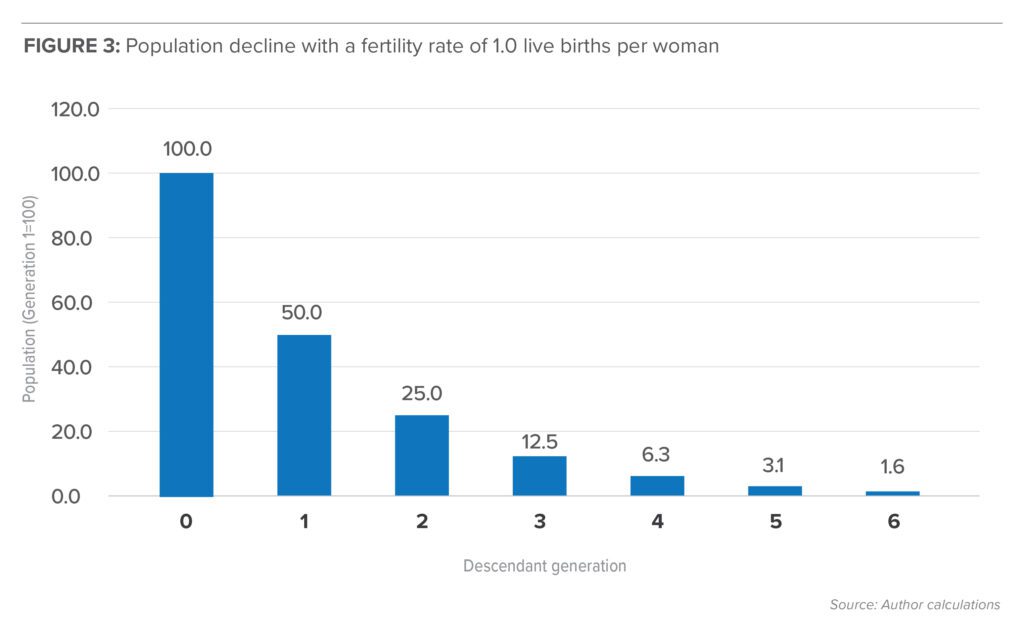

To illustrate the nature of the problem, Figure 3 shows the future for 100 members of BC’s native-born young adult population if a fertility rate of 1.0 persists for six generations. The fourth generation will be 94 per cent smaller and the sixth generation will be 98 per cent smaller than it is now.

Today’s young adults are the seventh generation since Confederation. A popular trope from Indigenous wisdom is that when making a decision society should consider the effect on the seventh generation to come. With a birth rate of 1.0, a group of 100 British Columbians today will be reduced to 1.6 in six generations. In other words, there won’t be a seventh generation.

Fertility rates are declining around the world, even in developing countries (Roser 2014). The fertility rate in the US fell below replacement rate in 2011 and is now at 1.6. In the anglosphere New Zealand is at 1.7 while, like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia are at 1.6. Many OECD countries are at 1.3 to 1.5. At 1.3, Canada has fallen below its peers in fertility. The global nature of this phenomenon puts limits on our ability to solve it by simply using immigration to raid other countries for their youth. It also means that the underlying trend is not strictly attributable to Canadian policy choices, but we do need to examine why the problem is worse in Canada than in countries that are our economic peers.

Most fertility research and analysis over the past century has focused on how to reduce it. There has been a great deal of effort directed at preventing unwanted pregnancies. But there has been very little attention paid to preventing the other unwanted outcome: reaching the end of one’s fertility without having had as many children as one had hoped for. Yet the survey evidence in Stone (2023) shows that for Canadian women, reaching the end of their child-bearing years with fewer children than they’d originally intended is many times costlier in terms of lost lifetime satisfaction than reaching it with more children than intended.

Over the next few sections, I will discuss why increased immigration is not a solution to the fertility problem. I will review academic research on drivers of fertility in developed countries and provide a multivariate analysis of the Canadian data. I will propose an action plan, and finally, discuss some potential challenges for a government that seeks to address this issue.

Immigration does not solve the problem

There are serious long term fiscal and societal consequences from a collapsing working-age population. Canada promises seniors a pension, free health care, assisted living and nursing home care, all of which get very costly in a person’s declining years. We are not replenishing our working-age population at a time when increased longevity is leading to an ever-expanding dependent senior population. This situation is not financially sustainable. According to the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis (CANCEA 2023), in the absence of mass immigration Canada’s dependency ratio (the ratio of the number of people too young or too old to work divided by the number of workers) will grow from about 50 per cent currently to about 60 per cent by 2030 and 70 per cent by 2050. At a 70 per cent dependency ratio every three workers are supporting two people who are too young or too old to work, requiring constantly increasing taxes to fund support programs, especially pensions, health care, and long-term senior care. The two major drivers of this trend are increasing longevity and the collapsing birth rate.

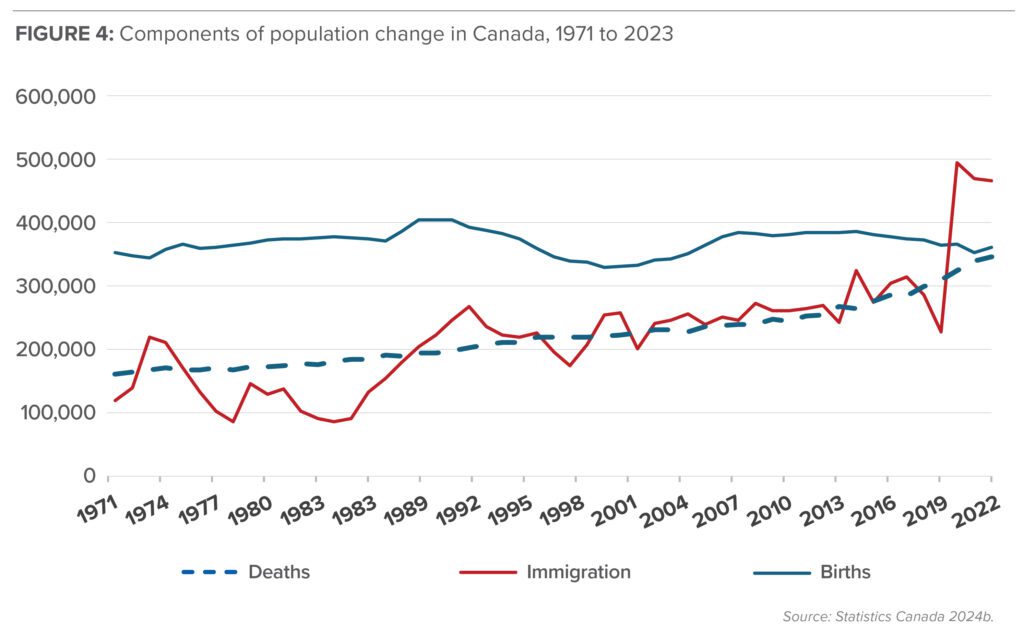

Canada has long welcomed large numbers of immigrants each year, but starting in 2021 the numbers soared. Figure 4 shows numbers of births, deaths, and immigration in Canada since 1971. For 50 years the number of immigrants arriving annually was roughly equal to the annual number of deaths. But in 2021 the numbers jumped such that annual immigration now exceeds deaths by 38 to 50 per cent. This was also the first year in which the number of immigrants arriving exceeded the number of domestic births.

This immigration surge has created significant problems, chief among them a housing affordability crisis (which is addressed in a separate volume in this series), depleted health care accessibility, and threats to social cohesion. Immigration is not a substitute for raising children here in Canada. The main problems with it are as follows:

- It is unfair for Canada to raid poor countries for their limited numbers of skilled and educated workers.

- The forces causing declining birth rates affect immigrants and domestic Canadians alike. In other words, when people move here from countries with high birth rates, once here they also tend to stop having babies. Trying to fix this with ever-more immigration amounts to a Ponzi scheme with people rather than money.

- A slogan once popular on the left was “the world needs more Canada” (CBC 2016). In the face of President Donald Trump’s taunts about annexing Canada many federal and provincial politicians have begun extolling Canada’s unique heritage and value as a country. If this rhetoric means anything at all it must mean that people born and raised under our heritage of culture and values are a positive force in the world. But only Canada can produce homegrown Canadians.

- Immigration does not fix the rising dependency ratio if governments allow young immigrants to bring their elderly parents with them. While family reunification programs may help promote domestic fertility among immigrants (since the grandparents can help with child care) the result is that we are importing a population whose age profile is not all that different from Canada’s, making the whole exercise pointless. In fact, it is worse than pointless, since it is unfair if Canadian seniors who worked their entire lives in Canada and paid high taxes to support our health care and senior care systems now find themselves at the back of a long queue of recently arrived elderly immigrants who have not contributed to the building of our social safety net.

Immigration, cultural diversity, and social trust

Mass immigration has long been viewed as a substitute for increasing domestic fertility. But it amounts to ignoring rather than solving the problems that create barriers to Canadians fulfilling their family ambitions. It also creates problems of its own. For one thing, at an extreme level it reduces Canada to nothing more than a giant hostel for foreign-born workers. This is the same as saying that Canada itself – namely, the historical and political entity formed at Confederation – has no intrinsic value. Those of us who see Canada as a great nation worth preserving want to see its culture and values passed on to new generations raised here in Canada.

Even if we didn’t need immigrants as workers, there is a school of thought that says that cultural diversity is an end in itself. But we must be careful with social engineering schemes. A large body of academic research argues that increased diversity is associated with declining social trust (e.g., van der Meer and Tolsma 2014; Demireva 2019). While there are uncertainties in the literature and some concepts are hard to define precisely, a large meta-analysis by Dinesen, Schaeffer, and Sønderskov (2020) concluded, “We find a statistically significant negative relationship between ethnic diversity and social trust across all studies.” The effect was particularly strong when they looked at increases in within-neighbourhood diversity, and provided support for Putnam’s (2007) “constrict” hypothesis in which people (of all races) whose neighbourhoods become more ethnically diverse tend to interact less and “hunker down” more. While the fragmentation can be overcome with time, the adjustment is slow.

In addition, mass immigration can end up being a threat to diversity, not a benefit. Picture, for example, a collection of spices in a kitchen cupboard consisting of little jars, each holding a single homogenous ingredient: cumin, basil, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, etc. The presence of many such jars makes possible an enormous diversity of cooking styles: French, Greek, Italian, Moroccan, Mexican, Thai, etc. Now suppose we observe that there is no diversity within each jar, so we take all the spices, stir them together in a big bowl, and refill every jar with the resulting mix. Each individual container is now “diverse” but we have destroyed the diversity of our menu. From now on every dish we cook will only ever have one flavour: the spice mix. The results may be tasty or revolting but either way our cooking will forevermore be monotonous.

The world is like that. Countries and regions are like spice jars. The presence in the world of places that are recognizably Chinese, Italian, Irish, Mexican, Quebecois, Moroccan, Russian, Texan, British, Scottish, Ghanaian, Brazilian, etc., makes it possible to experience a near infinite variety of cultures, ethnicities, and heritages. There are also, of course, Canadian regional cultures from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island to the Far North. But there has arisen in recent decades a line of thinking that says, in effect, every town must be turned into a human spice mix. Under this view it becomes imperative for every community to import a mix of people from around the world to create “diversity.” But doing so may actually destroy diversity, not enhance it, if every location becomes the same mix of global cultures.

People also want the option of making their home among whichever ethnic group they feel the most kinship and trust. This is a universal human preference, as the nicknames of many neighbourhoods in large cities (Chinatown, Little Italy, etc.) attests. The insistence on monotonous local diversity robs us of this option, which is one of the oldest instinctive desires of mankind.[1] The literature cited above on diversity and the breakdown of neighbourhood social cohesion relates to this point.

To summarize, there is a value in promoting domestic fertility as opposed to relying entirely on mass immigration to supply future generations of Canadians. This raises the question of how to do so, which is what the next two sections address.

Economic analysis of fertility changes

Some recent academic literature

Much of the post-war academic literature on demographic changes focused on how to reduce fertility, especially in low-income countries, but there is comparatively little on how to increase it. Many explanations for declining birth rates in advanced economies have appeared in the literature, including changing social norms, which have led to lower rates of marriage and family formation, increased educational and career opportunities (and expectations) for women, and episodes of economic uncertainty and weak income growth.

A recent study by Doepke et al. (2022) summarizes the current thinking on fertility drivers and argues that, for the world as a whole, while the income-fertility relationship was long thought to be downward-sloping (i.e., the higher a nation’s income, the lower its fertility rate), evidence now suggests it may be U-shaped such that at higher income levels increased income is associated with higher fertility. The study emphasizes “the compatibility of women’s career and family goals as key drivers of fertility.” The way we make daycare services available therefore matters, as we will discuss below.

A look at Canadian data

I assembled a database consisting of the following annual measures for all 10 provinces from 1991 to 2022:

- Fertility rates (Statistics Canada 2024b).

- Inflation-adjusted per capita incomes (Statistics Canada 2024c).

- Consumer Price Index – All items; Housing (Statistics Canada 2025a).

- Housing completions by type (Statistics Canada 2025b).

- Population of adults and adults in the 18 to 44 age range (Statistics Canada 2024d).

Each data series has 320 values (10 provinces times 32 years).

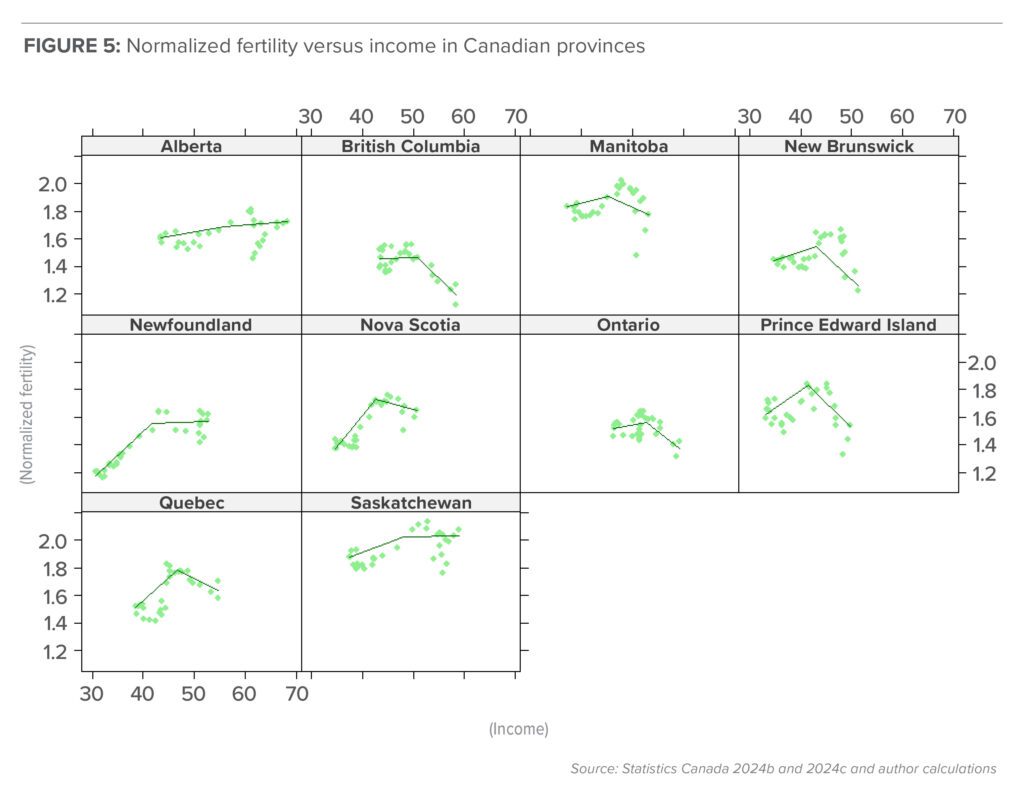

Because provinces have different demographic distributions, I normalized fertility rates as follows: I computed the fraction of adults in the 18 to 44 age range to serve as an index of the population eligible to have babies, then I adjusted these values to have mean of 1.0 across the pooled sample, then I divided the fertility rate by the resulting index. This means that, for instance, a province that has a low fertility rate but an above average senior population would have a slightly higher normalized fertility rate since part of its lower fertility is due to having a lower cohort in the baby-making age range. Figure 5 illustrates the results of these computations.

The comparison suggests that when considering normalized fertility levels, there is a positive relationship between income and fertility in the lower part of the income distribution, but it levels off or declines at higher income levels. This is opposite to the pattern discussed in the Doepke et al. (2022) paper based on global comparisons. However, the Canadian income distribution is in the upper portion of their global data set.

Since both fertility and income are co-trending, it is better to analyze patterns in the context of a multivariate regression model where the trending component can be separated out. I ran a multiple regression of the normalized fertility rate against the following variables:

- CPI(a): CPI – all items.

- CPI(h): % change in CPI – housing component.

- INC: Income (in thousands).

- INC2: Income squared.

- p: The total number of housing completions of all types per ’000 adults.

- f: The fraction of TOTAL.p consisting of apartments.

- YY: a time trend capturing the influence of common social and economic changes over time.

- PROV: a set of dummy variables that capture fixed effects by province.

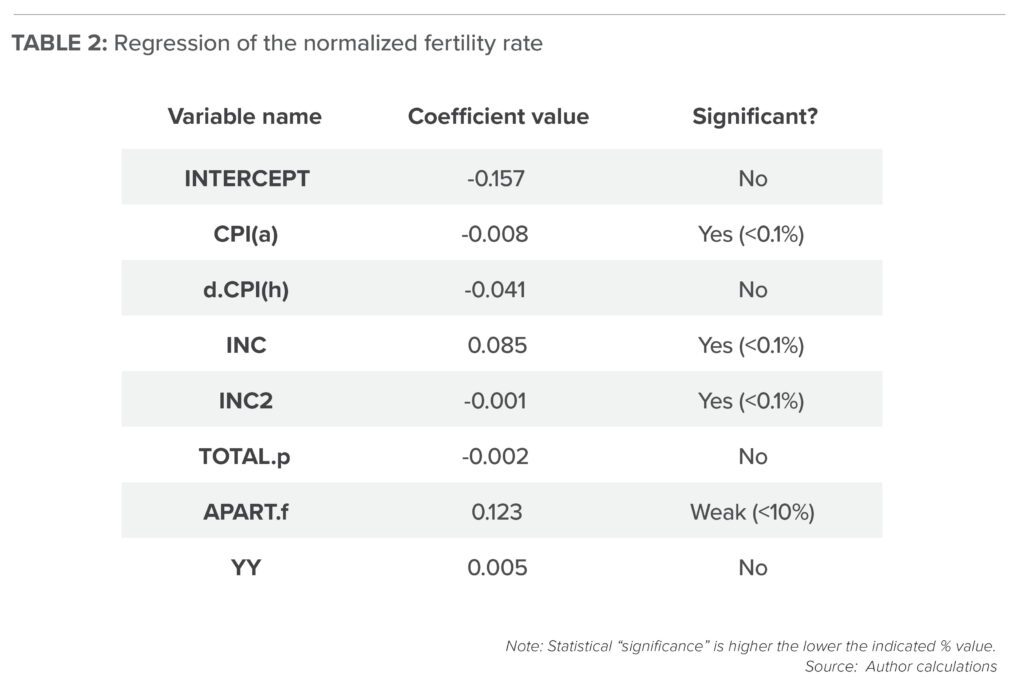

The regression results are shown in Table 2 (provincial fixed effect dummies are excluded).

The regression was 0.77 making the overall model highly significant. The coefficient results indicate the following tentative conclusions:

- Increases in CPI(a), the overall cost of living, suppress fertility. The effect is quite strong. A 10-point increase in the CPI (e.g., from 120.0 to 130.0) is associated with reduction in the fertility rate of just under 0.1. The shelter component of the CPI did not have a negative effect on fertility on its own, whereas the rate of change in housing costs had a negative effect, although the effect was insignificant. What this means is that while growth in housing costs on its own does not have a negative effect, an acceleration in the cost of housing does, although it is not significant.

- Income growth strongly benefits fertility. This confirms the survey evidence reported in Stone (2023). The regression results indicate that fertility rises with income across most of the sample, leveling out and declining only in the top few percent of the sample observations.

- The total number of housing completions per thousand persons has no apparent effect on fertility. This also echoes survey evidence in Stone (2023): housing costs matter but are relatively low on the list of reasons given for delaying child-rearing. However, the evidence shown here is that the fraction of housing units consisting of apartments has a beneficial effect on fertility. This may be capturing an effect related to the cost of entry-level housing units. So what matters is not simply the number of new homes but the types available. An abundance of apartments seems to be helpful.

- Even though the fertility data since 2016 show steep declines, the overall time trend from 1991 to 2022 is slightly positive. If no other explanatory variables are included the estimated trend coefficient would be 0.004 (significant). After controlling for income, cost of living, and housing effects, the time trend is about the same size (0.005) but insignificant. This is encouraging since the explanatory variables are things that can potentially be affected by policy decisions whereas the underlying trend may be difficult to change. After addressing the factors under our control, we may discover there is no underlying downward fertility trend.

The preliminary conclusions from this analysis are that to increase Canadian fertility rates we should focus economic policies that reduce the overall cost of living, increase real incomes, and increase the availability of housing, especially low-cost entry-level housing.

There are many limitations to this analysis and many remaining unanswered questions. For instance, it only looks at average overall fertility rates. It does not provide any insight into what might induce a family that already has one child to have a second or more. Also, the income measure used here is a per-person average rather than a per-household average. While the two are closely correlated, there is a separate question about whether the effects differ for male versus female earnings. Doepke et al. (2022) report that changes in male earnings have a relatively stronger impact on fertility. Finally, the survey evidence in Stone (2023) shows that non-economic factors also play a very large role in fertility decisions.

Guided by the empirical results the next section discusses policy options to increase the birth rate in Canada.

An action plan to increase domestic fertility

Many countries are now awake to the fertility crash and are trying to address it. Canada needs to join the effort. Effective measures to promote fertility will be costly both financially and in terms of political capital. Aggressive spending reductions across all levels of government are needed to free up funds to reward families that have babies. While the government needs to be prepared to spend some of its political capital on adopting a pro-natal policy, it should also recognize that if the arguments are well-thought through and skillfully presented, they will be popular with the majority of the population since they promote pride in our country and improve the welfare of families and children. Also, excessive immigration and high housing costs are very unpopular at the moment, which bodes well for this strategy’s prospects.

Part of the solution to our fertility crisis is, as noted, to address the housing crisis. A separate volume in this series presents an action plan for this predicament.

Canada offers parents direct, per-child cash payments through the Canada Child Benefit, a program that has been changed many times over past decades. However, Doepke et al. (2022) suggest that while such payments are helpful for alleviating poverty, evidence is lacking that they promote fertility.

A strategy to bring Canada’s domestic fertility rate back up could include the following elements:

Fiscal and economic measures

- Reduce the cost of living, especially housing and transportation costs.

- Lower marginal income tax rates, improve per-child benefits, and allow income-sharing.

Measures to make career and family goals compatible

- Improve income replacement schemes under EI.

- Take measures to increase the availability of private (including home-based) child care services.

Nudging social norms

- Take measures to shift social norms in favour of parenthood for both women and men.

Reducing the cost of living, especially housing and transportation

A separate volume in this series deals with housing (McKitrick 2025) while another will compile the various measures that governments could implement to bring down the cost of living. An overlooked issue is the need to reduce the cost of transporting children. A recent study found that car seat regulations significantly reduce fertility but do not increase safety outcomes for children above age 2:

“We show that laws mandating use of child car safety seats significantly reduce birth rates, as many cars cannot fit three child seats in the back seat. Women with two children younger than their state’s age mandate have a lower annual birth probability of .73 percentage points. This effect is limited to births of third children, households with access to a car, and households with a male present, where both front seats are likely to be occupied. We estimate that these laws prevented fatalities of 57 children in car crashes in 2017 but reduced total births by 8,000 that year and have decreased the total by 145,000 since 1980” (Nickerson and Solomon 2022).

A law that saved 57 lives at the cost of 8,000 foregone births is a bad law. The authors point out that originally safety seats were only mandatory for children up to age 3, but authorities have steadily ratcheted up requirements over time despite evidence showing they were no more effective than regular seat belts for preventing injury in children over age 2. The safety seat requirements should be scaled back. Designs should be permitted that allow three safety seats to fit into the back seat of a regular sedan, or the age requirements should be relaxed so that children are out of them sooner, i.e., at age 3.

Lowering marginal income tax rates, improving per-child benefits, and allowing income-sharing

The tax burden facing Canadians will be discussed in a separate volume in this series. One of the points it will emphasize is that the marginal effective tax rate[2] rises steeply in Canada even at low income levels. Most Canadians face 40 to 50 per cent tax rates on their income after the first few thousand dollars they earn. The volume will also show that marginal tax rates are worse for families with children than for single people. Addressing this problem is the focus of this section.

The government’s goal should not only be to lower the overall tax burden people face, but also to adjust specific provisions to encourage marriage and family formation. It also makes sense to encourage families who already have one or two children to have a third or more, since they have already acquired the child-rearing skills, cribs, and Lego sets. Quebec previously had a child benefit that rose with additional children but this has since been phased out (Cardus 2019). Countries engaged in aggressive pro-natal policies (like Hungary) are tying generous tax benefits to having more than four children. Options in this country might include:

- Partial income splitting for families with one or two children, increasing to full income splitting for families with four or more children.

- Increasing the tax credit for dependents and applying an increasing scale so that it is higher per child for families with 3 or more children.

The current dependant deduction is $4,999 per child. This could be raised to $8,000 for each of the first two children and $12,000 for each child after that, with the amount deductible against either parent’s income, so a family with four children would potentially pay no federal income tax on the first $40,000 of income. Canada implemented income splitting for married parents in 2014 but the newly elected Liberal federal government eliminated it in 2016 shortly after taking power (Cardus 2019). At the same time, the complicated maze of deductions for child care and related expenses should be simplified or eliminated altogether.

All these proposals have in common that they embed an implicitly positive message around having larger families.

Improved income replacement schemes under EI

Canada currently supports income-replacement programs and requires employers to hold a position for a mother or father taking parental leave. Employment Insurance (EI)-based income replacement options are generous in length (up to 84 weeks of total maternity and parental leave) but not in income: 33 per cent or 55 per cent income replacement depending on length of leave chosen; the parent must have been working prior to the child’s birth; there is a maximum $668 per week for standard leave ($34,736 annually) or $401 per week for extended benefits ($20,852 annually).

In the context of the family friendly tax breaks noted above, additional EI measures may not be necessary but should be considered. The expense of income replacement schemes is only incurred if parents have children. We should be so lucky if offering more generous maternity leave and fiscal inducements resulted in a heavier fiscal burden on the nation. One additional aspect that needs to be investigated is whether compensation to employers for holding positions for women on maternity leave is appropriate, and whether paying it might make a difference at the margin.

A national strategy to encourage private (including home-based) child care services

Both the quantity and quality of child care facilities affects fertility to some extent. Stone (2023) shows that concerns about child care cost and availability affect the likelihood of a Canadian woman having a child in the next two years, but when ranked among factors based on how commonly each was identified, it fell in the middle of the list, not at the top. Hence government spending on a national child care system may not have a commensurate payoff in promoting fertility. Also, the fixed-price programs offered by Quebec, Alberta, and the Canadian federal government have had an adverse impact on availability. The price cap and the need to run the service through a government-approved system had predictably negative impacts on supply, leading to wait lists and shortages. So, the programs may even have had a negative effect on child-bearing decisions.

If the government is going to take action to boost supply it should first widen the definition of caregivers as broadly as possible, starting with parents themselves. Government funding for caregiving should be evaluated against the alternative option of the mothers and fathers doing the child care work themselves. It may sometimes be cheaper simply to provide income support to a parent who takes time out of the workforce to care for children rather than going to work and needing daycare. For that reason, the strategy of boosting the dependent deduction rather than offering boutique tax credits for child care and child-rearing expenses is the appropriate place to start.

If the government wants to encourage an increased supply of child care services it should aim to make it as easy as possible for people to open good quality, professional facilities, including informal in-home services. This could involve:

- Providing a straightforward federal certification process based on the provider passing a skills test and their child care space undergoing an annual visit and passing inspection. The certification process should be voluntary (people would have the option of using non-certified providers if they chose), it should be contracted out to the private sector, and it should include a public listing of certified providers with publicly available client ratings.

- Providing instructional materials and skills-upgrading services to home day care providers prepared by qualified Early Childhood Education teachers.

- Let the market set the fees, and allow the fees to be HST- or PST/GST-exempt and not subject to income tax.

The challenge is to create conditions that help the market develop good child care options and to assist parents as appropriate without penalizing families who care for their own children at home. This can be accomplished by calculating what the value per child is of the current day care subsidies and paying them directly to parents whether they put their children in day care or keep them home. This could be accomplished by modifying the dependent tax credit to ensure that it at least covers the child care subsidy amount and is only clawed back at the marginal tax rate of the parent with the lower income so a non-working parent would get the entire amount of the subsidy.

Measures to shift social norms in favour of parenthood

Changes to social norms are not easy to measure, but they matter immensely and should be the focus of sustained government attention. The evidence shown in Stone (2023) indicates that non-economic factors play a large role in fertility decisions. In some cases, over the years, governments have embarked on campaigns to change public attitudes, as they have done with smoking and littering. This section proposes that we explore ways to shift attitudes in a pro-natal direction, nevertheless bearing in mind that we live in a free society.

The first thing to note is that the collapse of fertility is not uniform across society. Certain religious sub-groups have maintained high (or at least above-replacement) birth rates. It stands to reason that the birth rate is positively correlated with having a positive attitude to the making and giving of new life, and to being part of a culture that celebrates families who have multiple children. It also stands to reason that communities that encourage marriage and fidelity and discourage divorce will be associated with conditions that are more supportive for child-rearing.[3] There is also an intangible element to being part of communities in which all ages are present: many young adults with no such involvement rarely get practice holding and entertaining babies and eventually lose both the desire and skill set.

Much of the research on fertility trends focuses, understandably, on attitudes of young women towards child-rearing (such as Stone 2023). But there is very little information about the way attitudes of young men have changed over time. Stone (2023) reports that among women the lack of a suitable partner ranks more highly as a deterrent to having a child than child care costs, housing costs, the state of the economy, hours of work, and the lack of paid leave. There is a great need at present to understand what men perceive to be the main barriers to marriage and family formation.

Awards for parents

By increasing the marginal benefits to families with three or more children Canada would implicitly be celebrating the contribution of parents who take on above-replacement child rearing. But the celebration should also be made explicit. Canada should celebrate parenthood by presenting awards to women who have three or more children. For those with four or more a phone call and letter from the Prime Minister’s Office would be a tangible way of signalling the nation’s appreciation for the work of mothers and fathers in Canada.

Media representation of marriage and family

The federal government should not regulate private entertainment or communication, but at the same time it contributes a lot of money to the arts. There is scope for the government to ask content producers to make more content portraying marriage and family life in a positive light.

Potential challenges to implementation

There are conflicting narratives around family policy. On the left the narrative focuses on boosting female labour force participation, which conservatives criticize as being anti-family if it morphs into a social norm that disparages motherhood. Government involvement in day care is also criticized as “the government wanting to raise your kids.” Conservative measures to reward motherhood and promote a higher domestic birth rate will be criticized as oppressive to women and anti-immigration. The government will need to create a positive and unapologetic narrative around rewarding stable family formation and rewarding and celebrating the work moms and dads do in the lives of their children.

The government also needs to unapologetically promote the form of Canadian citizenship that is based on the experience of being born and raised in Canada. If we say that there is no distinction between being born and raised in Canada versus having just arrived from another land where they speak neither English nor French and their history and culture are completely different from ours, we are effectively saying there is no value to Canada as a political, historical, or social entity. That is, indeed, where the Trudeau-esque post-national ideology leads. If the government of Canada doesn’t want to promote that message it needs to articulate and defend the opposite.

Conclusion

Canada’s crashing fertility rate is a symptom of underlying problems that prevent Canadians from achieving their life and family goals. Rather than papering over these problems with ever-increasing immigration rates we should address them directly through a set of pro-natal policy reforms. This essay reviews evidence on factors that aid or impede domestic fertility and then proposes a series of policies that would benefit families and children. Key measures include improved deductions for dependents, EI-based income replacement, and income-splitting. There is also evidence that reducing the cost of housing and transportation will help. In view of the accelerating decline in our birth rates there is a need to move quickly on these challenges.

About the author

Ross McKitrick holds a PhD in economics from the University of British Columbia (1996) and is a professor of economics at the University of Guelph in Guelph, Ontario. He is the author of Economic Analysis of Environmental Policy (University of Toronto Press 2010). He has been actively studying climate change, climate policy, and environmental economics since the mid-1990s. He built and published one of the first national-scale Computable General Equilibrium models for analyzing the effect of carbon taxes on the Canadian economy in the 1990s. His academic publications have appeared in many top journals. He has also written policy analyses for the Fraser Institute (where he is a senior fellow), the CD Howe Institute, the University of Calgary School of Public Policy, and other Canadian and international think-tanks. In addition to his economics research his background in applied statistics has led him to collaborative work across a wide range of topics in the physical sciences including paleoclimate reconstruction, malaria transmission, surface temperature measurement, and climate model evaluation.

References

Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis [CANCEA]. 2023. An Uncomfortable Contradiction: Taxation of Ontario Housing. CANCEA. Available at https://www.cancea.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/CANCEA-TaxationOfOntarioHousing_2023.pdf.

Cardus. 2019. A Positive Vision for Child Care Policy Across Canada: Avoiding the Social and Economic Pitfalls of “Universal” Child Care. Cardus Institute, January 2019. Available at https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/A-Positive-Vision-for-Child-Care-Cardus-Family.pdf.

CBC. 2016. “Obama: ‘The World Needs More Canada.’” CBC News, June 29, 2016. Available at https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/video/1.3659172.

Demireva, Neli. 2019. Immigration, Diversity and Social Cohesion. Briefing. University of Oxford, Immigration Observatory. Available at https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Briefing-Immigration-Diversity-and-Social-Cohesion.pdf

Dinesen, Peter T., Merlin Schaeffer, and Kim M. Sønderskov. 2020. “Ethnic Diversity and Social Trust: A Narrative and Meta-Analytical Review.” Annual Review of Political Science 23: 441–465. Available at https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052918-020708.

Doepke, Matthias, Anne Hannusch, Fabian Kindermann, and Michèle Tertilt. 2022. The Economics of Fertility: A New Era. Working Paper No. 29948. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29948/w29948.pdf.

Kierney, Elisabeth. 2023. The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind. University of Chicago Press.

McKitrick, Ross. 2025. “Canada at a Crossroads – Volume 1: The Housing Crunch.” February 11, 2025. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/canada-at-the-crossroads-volume-1-housing/.

Nickerson, Jordan, and David Solomon. 2024. “Car Seats as Contraception.” Journal of Law and Economics 67, 3 (August). Available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/731812.

Provencher, Claudine, and Nora Galbraith. 2024. Fertility in Canada, 1921 to 2022. Catalogue no. 91F0015M. Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/91f0015m/91f0015m2024001-eng.htm.

Putnam, Robert D. 2007. “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty‐First Century.” The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies 30, 2 (June): 137–74. Available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x.

Roser, Max. 2014. “Fertility Rate.” Our World in Data. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/fertility-rate.

Statistics Canada. 2024a. “Table 13-10-0418-01: Crude Birth Rate, Age-Specific Fertility Rates and Total Fertility Rate (Live Births).” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310041801.

Statistics Canada. 2024b. “Table 17-10-0008-01: Estimates of the Components of Demographic Growth, Annual.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000801.

Statistics Canada. 2024c. “Table 11-10-0239-01: Income of Individuals by Age Group, Sex and Income Source, Canada, Provinces and Selected Census Metropolitan Areas.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110023901.

Statistics Canada. 2024d. “Table 17-10-0005-01: Population Estimates on July 1, by Age and Gender.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501.

Statistics Canada. 2025a. “Table 18-10-0005-01: Consumer Price Index, Annual Average, not Seasonally Adjusted.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000501.

Statistics Canada. 2025b. “Table 34-10-0126-0: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Housing Starts, Under Construction and Completions, All Areas, Annual.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3410012601.

Stone, Lyman. 2023. She’s (Not) Having a Baby: Why Half of Canadian Women Are Falling Short of Their Fertility Desires. Cardus Institute. Available at https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/reports/she-s-not-having-a-baby/.

van der Meer, Tom, and Jochem Tolsma. 2014. “Ethnic Diversity and Its Effect on Social Cohesion” Annual Review of Sociology 40: 459–478. Available at https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043309.

No comments:

Post a Comment